DeathWrites Blog

Lucy Claire Christopher: Sitting in The Sadness: Reading and Writing Love and Schizophrenia | 12 September 2023

In this longer reflection on grief, love, and writing, Network member Lucy Christopher takes us through the process of writing about her late father’s experience of schizophrenia, using his own words from his self-published memoir.

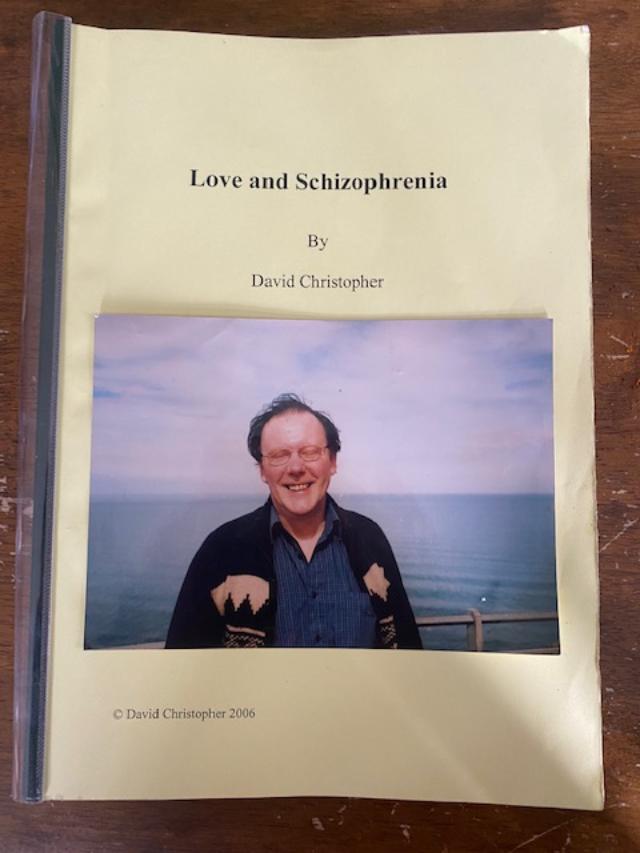

When I told my brother I was going to write a book about our Dad, incorporating writing from Dad’s own memoir Love and Schizophrenia, he suggested I might want to access some therapy to help with the process.

“Nah.” I dismissed the idea. I don’t actually find this stuff very upsetting, I told him confidently, with the characteristic self-denying foolishness I flatteringly thought of as stoicism.

My recently deceased father, who died after a year of lockdown living alone—an extreme form of isolation—in a home he could no longer look after, in a body which made small essential tasks painful and challenging, with a mind that we who loved him struggled to connect with or understand, his telephone missives increasingly angry and paranoid as we asked him, indeed urged him, for his own health, not to go to the pub and see another human face.

And his book, which detailed his experiences of psychosis and internment by the State multiple times, detailed descriptions of the poverty and madness that I had watched him contend with throughout my childhood. Writing my own book about all that?

“Nah,” I said. I don’t actually find this stuff upsetting.

“Nah.” I dismissed the idea. I don’t actually find this stuff very upsetting, I told him confidently, with the characteristic self-denying foolishness I flatteringly thought of as stoicism.

My recently deceased father, who died after a year of lockdown living alone—an extreme form of isolation—in a home he could no longer look after, in a body which made small essential tasks painful and challenging, with a mind that we who loved him struggled to connect with or understand, his telephone missives increasingly angry and paranoid as we asked him, indeed urged him, for his own health, not to go to the pub and see another human face.

And his book, which detailed his experiences of psychosis and internment by the State multiple times, detailed descriptions of the poverty and madness that I had watched him contend with throughout my childhood. Writing my own book about all that?

“Nah,” I said. I don’t actually find this stuff upsetting.

*

By ‘The Sadness’ I do not mean the day-to-day intrusive thoughts, the machinations of what I think of as my Guilt-Grief, that ever-present gnawing sensation that more could have been done to help him, to love him, to save him—specifically, that I could have done more to help him, to love him, to save him. The regret that I didn’t take him out to places where he could sing. After all, he loved to sing, and other people loved to hear him sing, so why? That stuff is just there and it ebbs and flows as I alternate between thought exercises - even if I had known of problem A, and was able to fix that, there still would have been problems B and C, shuffling around cards marked Dementia, Disability and Psychosis - to doing everything possible to push the thoughts away with books, alcohol, podcasts, alcohol, social media, alcohol, etc., on repeat ad-nauseum.

Eventually, though, when I run out of distractions and plunge my body into the pool at my local gym, devoid of diversions, I end up back at Dad - every time. That stuff isn’t going anywhere.

*

I circled round the material, the memoir my Dad wrote, had copies bound, and distributed to friends and family, my subconscious obviously more wary than I was letting on. I amused myself by comparing the number of mentions of me versus mentions of Stephen to back up my own theory of favouritism, but gave up when the balance wasn’t as skewed towards the first born son as I had imagined it to be. Part of my theory had come from my Dad’s own schizophrenic delusions. Stephen, with his perfect circle birthmark right in the centre of his forehead, was the reincarnation of the Buddha while I, naturally, was Lucifer. I’m not sure how Stephen being Buddha fits with my Dad’s belief that he was Jesus Christ, but his mother had been called Mary, a fact which for Dad sealed the deal - case closed. Buddha, Lucifer and Christ kicking about a wee flat in Edinburgh’s St Stephen Street. I took a screenshot of the following sentence about some summer day in the early noughties and sent it to my brother, asking if Dad was throwing shade and suggesting I was A Pie:

Long journey back to Edinburgh with holiday stories and eventually, trust Lucy, a lunch in a Pizza Hut.

*

When talking about the project, I was keen to let people know it wasn’t just heavy, it was funny. Like Limmy’s iconic tweet for deceased celebrities, I wanted you to know my memoir about my dead Dad was actually down to earth and VERY funny. Everything to avoid The Sadness. The specific sadness around my feelings about my Dad is that he was unfortunate to experience extreme levels of mental and physical pain throughout his life. I pick it up, I pop it back down. An exploration of years of pain, something tender I dare not prod.

*

My Dad had a rare skin condition called Epidermolysis Bullosa – E.B. for short – which is described by the charity DEBRA as ‘butterfly skin’: the skin becomes so fragile it can tear or blister at the slightest touch. It can be extremely painful. My dad had it on his hands and feet. It is therefore astounding that the condition and the pain it caused him is barely mentioned in the book. He describes the ‘victimisation’ he experienced at boarding school due to his condition. He also describes my mother calling him after my birth – her in the payphone at Elsie Inglis maternity hospital, him sectioned at the Royal Edinburgh – and asking her if I had the skin condition. He says, ‘I was so relieved to hear No’.

Although significantly painful, in his book his skin is always secondary to the enduring and confusing pain of psychosis, depression and anxiety. In his late teens, he describes something in his brain ‘snapping’ and changing forever. He cannot connect with his girlfriend, Jane, becoming paranoid and withdrawn. Of this time, he writes: ‘First love has ceased but it had happened inside my head and I had no idea how, but it had left me raw and in pain almost all the time.’

*

At Dad’s funeral, Stephen spoke about Dad’s relationship with pain. So much physical pain, so much mental pain. Of the physical, he rarely complained. The skin so sensitive it blistered at the slightest touch. Dry mouth. Worn away hip. Feet with E.B, too sore to walk. Medications. Sleeplessness, restlessness, anxiety. Oh, such anxiety. A voice at the end of the phone when you called him – as soon as he heard the telephone ring he ran towards it every time from anywhere in the flat, be it his bed or when stirring soup on the hob – an out of breath and frantic “Hello!” and a “Lucy! Are you ok?” Out of breath. “Yes, Dad”, I would sigh. “I’m fine! Of course I’m fine.”

*

He was everything all at once. He was gentle, kind, generous, funny and modest. He could also be furious, stubborn, egotistical. Engaged with you, yet always a distance removed. I think about him at school, being bullied for the skin condition he couldn’t help, which also meant he was spared the strap. I believe that regardless of the schizophrenia it had shaped him in some profound way, gave him a toughness somewhere that you couldn’t get past, a self-protection barrier.

*

I avoid The Sadness, until I can’t avoid it any longer. I sit in a garden centre cafe near my mum’s home in Kelso, reading my Dad’s words. The café is perfect for my purposes - huge with loads of tables so you get left alone in a corner to cry over a pot of tea for two-and-a-half hours. I’m back with Dad in the Seventies in Glasgow, as he becomes more alienated and ill, trying so very hard to be normal, to succeed in his studies at the Conservatoire, before being chucked out. He writes that somewhere in the back of his mind at this time he thought it might be schizophrenia, but the possibility frightened him too much to do anything about it.

He also had another painful affliction - one suffered by many. He had wanted to be a famous musician, and while he was very talented, he was never ‘discovered’, was not a Beatle or a Stone or even a Kink. He writes, ‘I just wanted to be a rock star like half the world then, it seemed. Quite sad really, in the old sense. I was longing inside for the old days and my ex-fiance.’

*

I stay with Dad in the Seventies for all of the next week. Wandering around where he used to live in Glasgow’s West End, thinking about him trying to work out what was happening to him. Drifting out at work meetings, thinking about Dad going to London to ‘make it’ and ending up selling carpets in Harrods and joining a religious cult. In his words, there is youthful alienation, and fear. Years on the fringes, living on the margins. I connect with Dad’s pain and with my own buried pain – I know how it feels to think the world is going on without you. I once felt lost too.

*

When I was at the University of Glasgow, I would phone my father to talk through my loneliness, my heartbreak and pain, my own youthful alienation. He would laugh gently and tell me about his student job as a night time driver for the pharmaceutical services, delivering pills all over the city. It’s hard to remember, because he became so detached in the years before his death, but my Dad was a great source of solace and advice to my younger self. He would buoy me up, and talk me down, reassuring me at all times that I was made of Great Stuff. He was right.

I don’t know why I let myself suffer so much. I just thought it was normal.

*

For years I have taken my daily 20mg of fluoxetine and got on the bus to work, convinced that if I did all the right things and took care of the people I loved, then everything would be ok. Wallowing was indulgent, and an indulgence only youth could afford. In telling myself that story, I could conveniently also avoid processing painful memories. However, there can be healing in sadness too. In avoiding it constantly, we short change ourselves and block the healing lessons of life, the opportunity to change and grow.

In order to write this book, I would need to sit in The Sadness for a while, and that wasn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Lucy Christopher is an Edinburgh born, Glasgow based writer. Her interviews and articles on arts and culture have appeared in The Skinny, The Wee Review and The Leither.

Follow Lucy Claire Christopher on Twitter @LUCYCCHRISTOPHE

Listen to the music of Dave Christopher here: https://davechristopher.bandcamp.com/music

Follow Lucy Claire Christopher on Twitter @LUCYCCHRISTOPHE

Listen to the music of Dave Christopher here: https://davechristopher.bandcamp.com/music