DeathWrites Blog

Kris Haddow: An Appendix of Grief: writing through illness, recovery, and loss | 28 February 2024

Kris Haddow charts the changing face of his DeathWrites project after a drastic health scare.

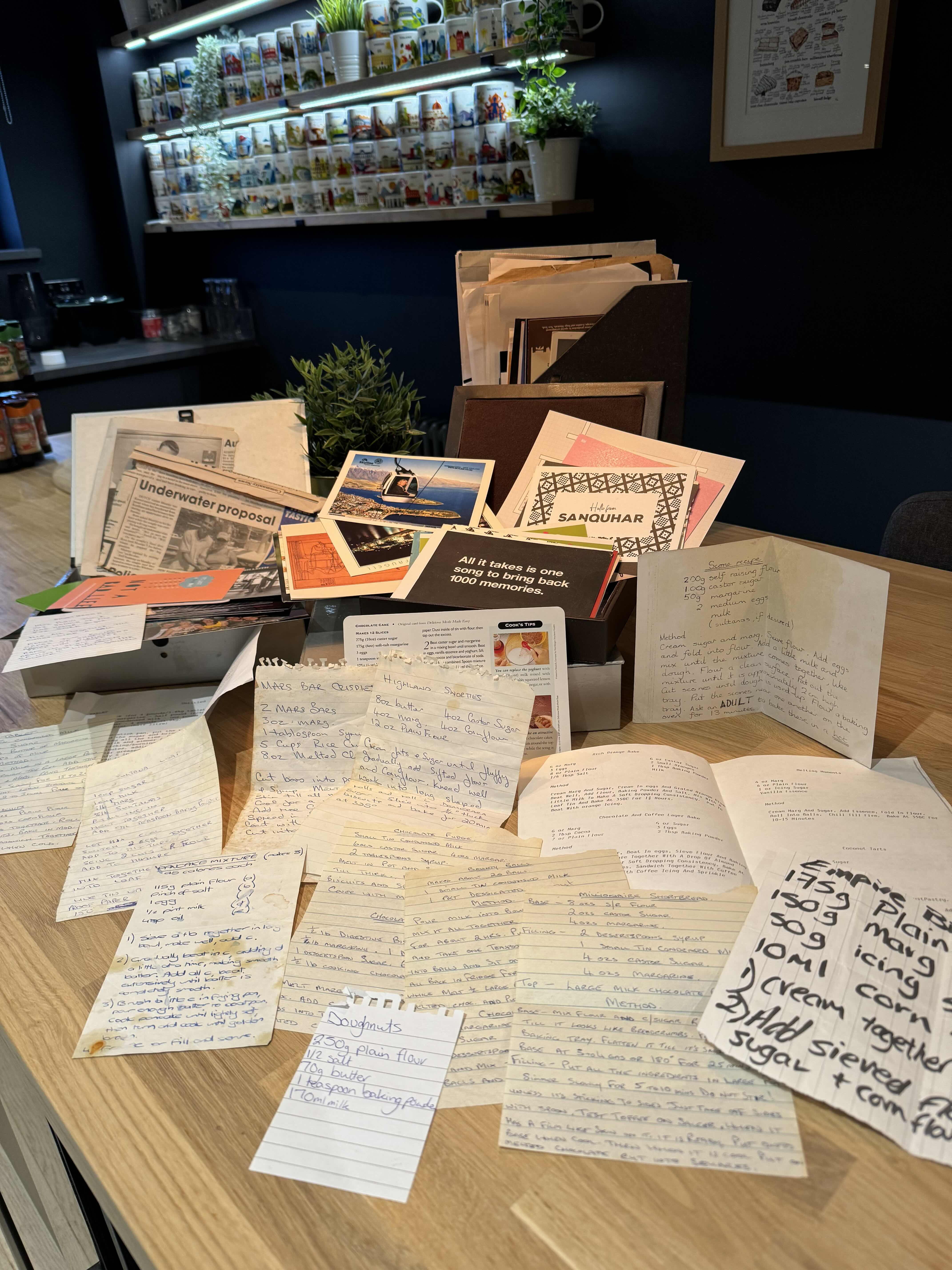

For over two decades, I have squirrelled away materials in journals and box files—articles, book and movie quotes, letters, postcards, photographs. These curios act as keys, unlocking memories; like an index, helping me recollect those I have loved and lost.

When I joined the DeathWrites Network in early 2022, I named my project ‘An Appendix of Grief,’ and began writing responses to items in my collection.

Today is a significant anniversary for me. It is exactly a year since my world flipped upside down, with a terrifying and ironic twist of fate.

On it is her recipe for the brownies I loved. I didn’t know it was there.

I read letters and emails from my auntie in Australia. I lived with her in my early twenties, and we remained especially close. In her final months of palliative care at home, we spent precious time together before she entered the hospice. Cancer took her a few short weeks later. I pick through photos from her trip to Istanbul in 2003; find the thistle brooch she wore to my play in 2011. Folded alongside are pages from her battered copy of Scottish Recipes (1968). One is for drop scones, the other for tablet.

When I joined the DeathWrites Network in early 2022, I named my project ‘An Appendix of Grief,’ and began writing responses to items in my collection.

Today is a significant anniversary for me. It is exactly a year since my world flipped upside down, with a terrifying and ironic twist of fate.

*

During the first year of my project, the research proves as tough as the writing. I dip into my archives for inspiration. A yellowed page falls loose from a chapbook gifted to me by my friend, the poet Mary Smith, who I met on a summer school in the 90s; Mary later got me a development job with her husband, so often fed me meals, fed me poetry.On it is her recipe for the brownies I loved. I didn’t know it was there.

I read letters and emails from my auntie in Australia. I lived with her in my early twenties, and we remained especially close. In her final months of palliative care at home, we spent precious time together before she entered the hospice. Cancer took her a few short weeks later. I pick through photos from her trip to Istanbul in 2003; find the thistle brooch she wore to my play in 2011. Folded alongside are pages from her battered copy of Scottish Recipes (1968). One is for drop scones, the other for tablet.

Again, I rummage. Out falls a postcard with “All it takes is one song to bring back 1000 memories” printed on the front—on the back, I have scribbled this, from Forrest Gump (1994):

Mama always said, dying was a part of life. I sure wish it wasn't.

I put the boxes away.

Writing can wait.

*

My other writing project—a crime novel—takes me to Aberdeen for Granite Noir in February 2023. I see friends, attend panels and talks; a fellow Network member launches their new book. It is all very exciting.

But I don’t feel great.

I ignore it at first, assuming it’s the unwelcome spectre of burnout from my old corporate job. I have, after all, been overdoing it again.

On Sunday, I leave the festival early and drive home to Glasgow.

An increasingly painful stitch develops in my side. I am forced to make several layby stops to catch my breath, icy air cloying at my lungs. I presume I’ve eaten something dodgy or slept in a funny position in the strange hotel bed. The pain doesn’t relent.

Back home a few hours later, I become violently sick. I crawl to the sofa, sleep fitfully and feverishly for several hours, then black out completely until Monday morning. I almost fall on my staircase, my stomach excruciating. I call 111, and am still on hold a while later when I remember there has been strike action, that the news said the NHS is overwhelmed. I try ringing my GP surgery instead, and eventually get through.

I’m told the first appointment is a week on Thursday—ten days later.

I’m in agony, I tell the receptionist. I hate to be a bother, but I couldn’t get through on 111, and didn’t want to dial 999 needlessly. She asks me to repeat where the pain is, I hold, then I have my GP’s attention. He is concerned. He immediately refers me to the surgical unit at Glasgow’s Queen Elizabeth University Hospital. He says waiting for an ambulance could be risky, and orders me a cab.

*

After hobbling through reception, my blood pressure is checked.

They ask if I need painkillers.

I join the throng of waiting patients, and I wait.

Seven or eight delirious hours pass.

I am finally sent for scans, then returned to the waiting area where I wait, and I wait. It is so late now the room is near deserted, just three of us left.

Then, several nurses and a surgeon descend on me out of nowhere, alert, and with urgency. My appendix may be rupturing, they say, it must come out. It will likely be keyhole surgery, but I must wait ‘til morning for theatre.

They try to make us comfortable for the night, but there are no beds available; we are tucked under thin sheets on gurneys in a recess off the corridor. Beside me, a surprisingly stoic woman with an ectopic pregnancy, and a man who looks green, who hardly speaks, who weeps in the darkness in the wee small hours.

Sleep is difficult. There is too much noise. A bitter February draught cuts deep every time the doors burst open.

*

I awake to a dozen or so tubes in my arms, my legs, in places I can’t feel or reach. It is not the time or day I expect. A nurse tells me things haven’t quite gone to plan—I’m in a critical care ward having undergone major surgery. In addition to my appendix, other bits have been removed, along with a ‘substantial mass’ they found whilst in there. That part isn’t fully explained.

I’m still heavily sedated, and don’t think to ask questions, too distracted by a memory of my Nana who I’d been dreaming of mere minutes before.

It is later that I learn the full extent of my injuries; much later still before the ‘C’ word is dropped.

*

I am fortunate to have the support of family and friends during my recovery. They take turns visiting. Some stay over to help cook and clean as I convalesce. Not for the first time in my life, people feed me food, feed me stories, keep me nurtured.

One afternoon, I am chatting to Mum about how long it's been since I baked back home. I always enjoyed it, this creative act of another variety, but had all but stopped after going vegan in 2016. Most of my old recipes used ingredients no longer suitable for my diet.

An idea comes.

I begin searching the archive, seeking out those recipes I’d tucked away. Mum looks for others back home; Dad is dispatched to the shops.

While I’m still a little wobbly, I’m able to potter around my kitchen with my parents’ help. Over several weeks, I recreate the methods and flavours using plant-based alternatives.

Brownies. Carrot cake. Drop scones. Shortbread.

Some attempts are less successful, but we refine them with a bit of help from the internet. With each recipe I revive and eventually perfect, I record memories of the loved one who shared the original.

On the other side of my near brush with death, I begin to write through my recovery, tackling bereavements I’ve long wrestled with, honouring those I’ve lost.

*

Two months after discharge, the physio says he’s happy with my progress and to see me gaining weight.

(I don’t have the heart to tell him how, but after sampling my latest batch of tablet, I reckon he knows.)

*

A year on, I am doing well.

I almost wrote fine, but am conscious of not doing that typically male, typically Scottish thing of deflecting my feelings or minimising the severity of my health scare.

For a while last year, I wasn’t doing so great. Not that you’d have known had you not seen me in person—my carefully curated social media posts presented my happier, wisecracking persona, the extroverted part of me feeling obliged to maintain some semblance of normality for show.

A writing colleague tells me they’re delighted to see me active again, wondering how on earth I’ve found the energy to juggle trips and travel so soon after surgery.

My façade cracks. For the first time, I confess I’d been working my way through my bucket list after my diagnosis, just in case.

Just in case.

*

In December, after six agonising months, I finally move up the waiting list for long-awaited scans. I’ll omit the medical detail and complication, but the results are good, with my surgery signed off as successful. It looks like I’m on track for an all-clear.

My appendix may have caused me more than my share of grief last February, but had it not, the other issues may not have been caught so early, and the prognosis might’ve been a lot worse.

I may never fully bounce back to my old fitness levels or self, but I’m at peace with that now. I like the man I am becoming. I’m adjusting to a new pace of life, still have dreams and goals to pursue, still find joy in simple acts, like writing and baking.

More than anything, I look forward to sharing my purvey of sweet treats and the stories of the people behind them. It no longer feels like I’m curating an appendix of grief.

Gradually, it’s becoming a record of love.

Kris Haddow is a playwright, poet, performer and author from Dumfries and Galloway who has won awards for his Scots dialect writing. A University of Glasgow MLitt Creative Writing graduate, he is currently writing his first novel while researching Lallans and South West Scots representation in publishing in pursuit of their DFA. Kris is a Scottish Book Trust Ignite Fellow in 2024.